Chief Niwot's Curse

I invite you to a local event in December 2024 for a close look at one of my artworks, as well as those of my school peers

A painting I created last fall at Front Range Community College was just accepted into the juried student art show at the Firehouse Art Center in Longmont, Colorado, opening for about a month starting on Friday, December 6. (On exhibit there now through December 1 is “Hang Time,” featuring artworks by Firehouse Art Center members including a brilliant former classmate, Robyn Eubanks. Stop by—the works vary wildly and are always worth a look.)

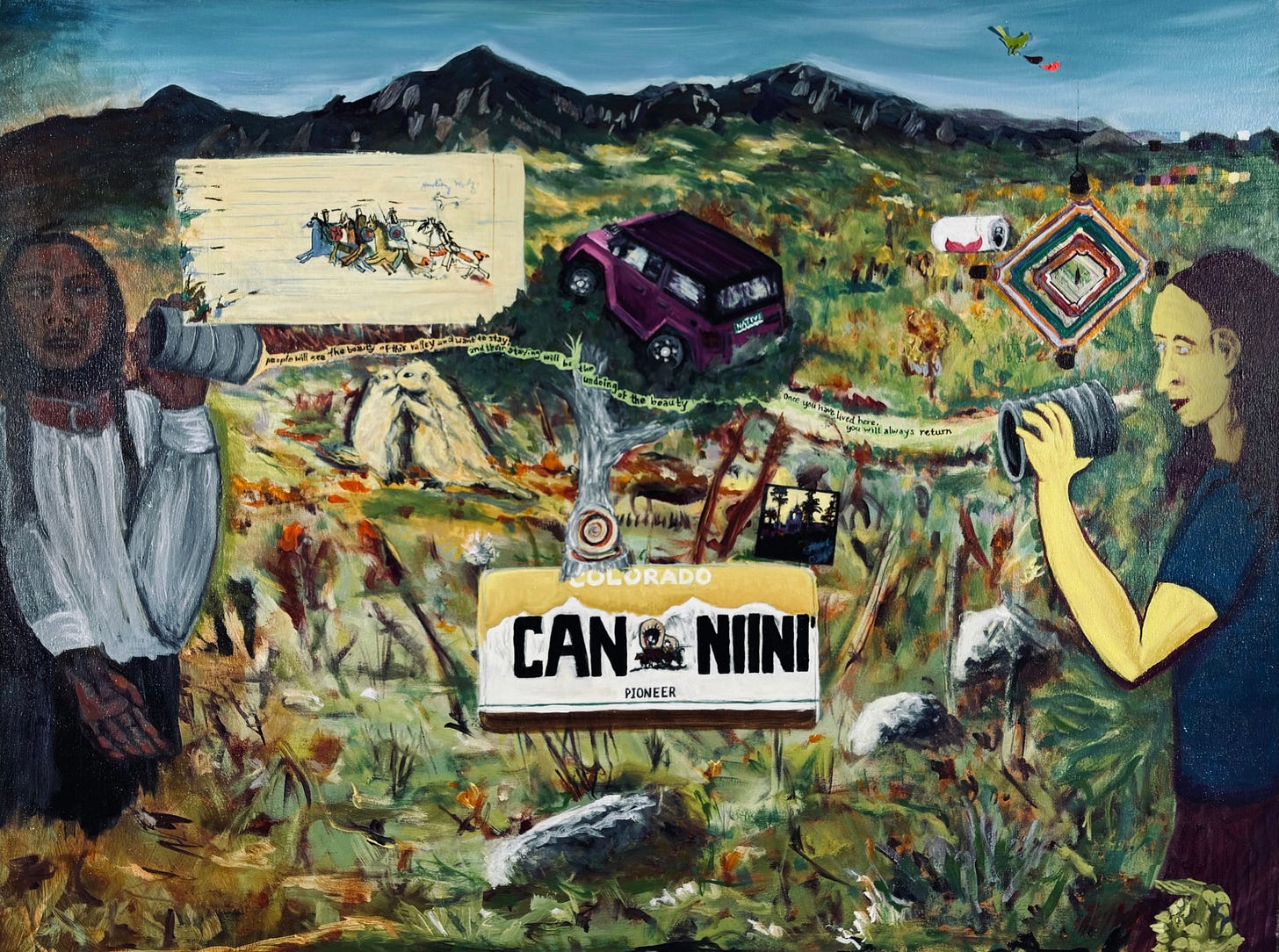

This painting is called Chief Niwot’s Curse and was a response to the “layered imagery” assignment in Painting 3. I first took this large (roughly 36 x 48") canvas to a field in Boulder south of Valmont and east of Foothills Parkway to do a plein aire painting of the foothills and rolling terrain. It was fun to put in the big things first—the line of the mountains, then the shrubs, greenery, and rocks, getting more specific as I worked toward the foreground.

When I started the painting, I had “Chief Niwot’s Curse” in mind, which has two variations I know of. I grew up in Boulder and the one I always heard was “Once you have lived here, you’ll always return.” Later I learned a different version—what Chief Niwot actually proclaimed back in the days when he was trying to negotiate peace treaties with the white settlers moving here from points east: “People will see the beauty of this valley and want to stay, and their staying will be the undoing of the beauty.” I envisioned the children’s circle game of “telephone” played through time, in which the message whispered to the next person gets slightly garbled and retold to the next until the final recipient says what they heard, which usually sounds nothing like the initially murmured message. So I put cans in the hands of my Chief Niwot figure and the modern woman on the right, as if they were using tin cans to talk to each other across many decades.

I also gave Chief Niwot/Lefthand two left hands. Even this has special significance to me as I am left-handed. I started attending an elementary school in town in sixth grade where one of the fifth-grade teachers was still hitting students’ left hands with a ruler when they used them to write. I was always grateful I never suffered under that teacher’s bizarre idea of “right and wrong” and felt for my fellow left-handed kids who’d had to endure that treatment and resist their natural impulses.

Wrapping my head around the “layered imagery” assignment wasn’t easy. One of the challenges set by our professor, John Cross, was to create a space but then to “break the rules of that space” by layering objects that couldn’t really exist together in one plane. At first my painting looked like a landscape with a lot of stuff littering it, but as I painted new layers, I started to get a feel for breaking the spatial rules.

When I was a kid growing up with my Boulder hippie parents, and listening to all kinds of music including The Eagles’ Desperado and Hotel California albums on repeat, I identified with the pioneers, who had struck out to find new horizons and new treasures. My parents moved from Denver to San Francisco with me and my sister, Baby, when I was three, so I really identified with the people who migrated to California to find gold. We moved back to Colorado when I was six and I stayed until graduating from high school, when I returned to California for about 15 years before settling once again in Colorado (exemplifying the modern-day version of Niwot’s “curse”). When I did some genealogy research and discovered a grandfather I hadn’t known was born in Denver, I once thought I’d like to have a Colorado Pioneers license plate, and thought perhaps I’d put one of those green-and-white “Native” stickers on my car one day.

Over time, however, I began to feel that the notion of the plucky pioneer obscured the fact that my ancestral white settlers took the land that didn’t belong to them. Even though I was born in Colorado and live here now, I no longer felt displaying a “Native” sticker would be appropriate, given the way the true indigenous peoples have been driven from the places I’ve lived.

I kept hearing not only the “Hotel California” line, “You can check out any time you like, but you can never leave,” but also the line from “The Last Resort,” the final track on the album: “You call some place Paradise, kiss it goodbye.” So I copied the cover of the album onto the painting as one of the layers.

The diamond-shaped object is what we called a “god’s eye” when we were children and made them at school by wrapping two crossed sticks in different colors of yarn and hanging them in a window or on a wall.

Because cans figure in the painting, I added the word “CAN” to the license plate. I looked up Cheyenne words and added a translation of can (in the sense of able) to the right side of the license plate. I had recently learned that canned kombucha isn’t as healthful as bottled, so I put an empty kombucha can on its side.

I watched prairie dogs popping up from their burrows and interacting while I was painting the plein air layer, so I added a pair of kissing prairie dogs. Prairie dogs are rodents living in the fields all over the area and we are always displacing them to build new buildings and roads and parking lots, but they’re amazing animals with complex observation and language skills.

The felled tree was a specific tree I saw cut down and eventually removed when trees were cleared on Iris Avenue and 28th Street for the new construction at Diagonal Plaza. The magenta Jeep was a nod to both the cornucopia of cross-branding associated with the Barbie movie popular at the time I made this painting and to my cousin, who takes his SUVs four-wheeling in all sorts of stunning environments.

As I thought about all of these objects and their meanings, I realized that I had been closing in on the deadliest day in Colorado’s history: The Sand Creek Massacre. A group of 675 men in the US Army, led by Colonel John Chivington, on November 29, 1864, ambushed, killed, and mutilated an encampment of Cheyenne and Arapaho people who had been living on the banks of Big Sandy Creek. Many warriors were killed, but so too were many women and children. My art history class had recently introduced me to ledger art, illustrations indigenous artists made using papers from ledger books and other discarded fabrics and papers. I had a sore, heavy heart as I worked at copying some of Howling Wolf’s ledger-paper picture of the shooting of distinguished warriors on horseback by a horde of Army soldiers.

Making this layered imagery painting deepened my understanding of the history of my home state and my place in it. If someone purchases this painting, I will contribute part of the proceeds to the people who lost so much when my ancestors arrived, broke treaties, and built edifices they proclaimed their own.